Co-Designing a Community Digital Ecology

A socio-technical system that strengthens local food resilience, supports learning, and nurtures community-driven farming innovation.

As a team, we were tasked with developing a digital substrate to support the living system rhythms of Ireland's GrowDome initiative, where grassroots growers, environmental data, and community events interconnect in a regenerative agri-social network. Rooted in real needs and designed for scalable learning and community care, we built a socio-technical system to support local food resilience, community learning, and the rhythms of hydroponic growing - years ahead of the agri-tech hype.

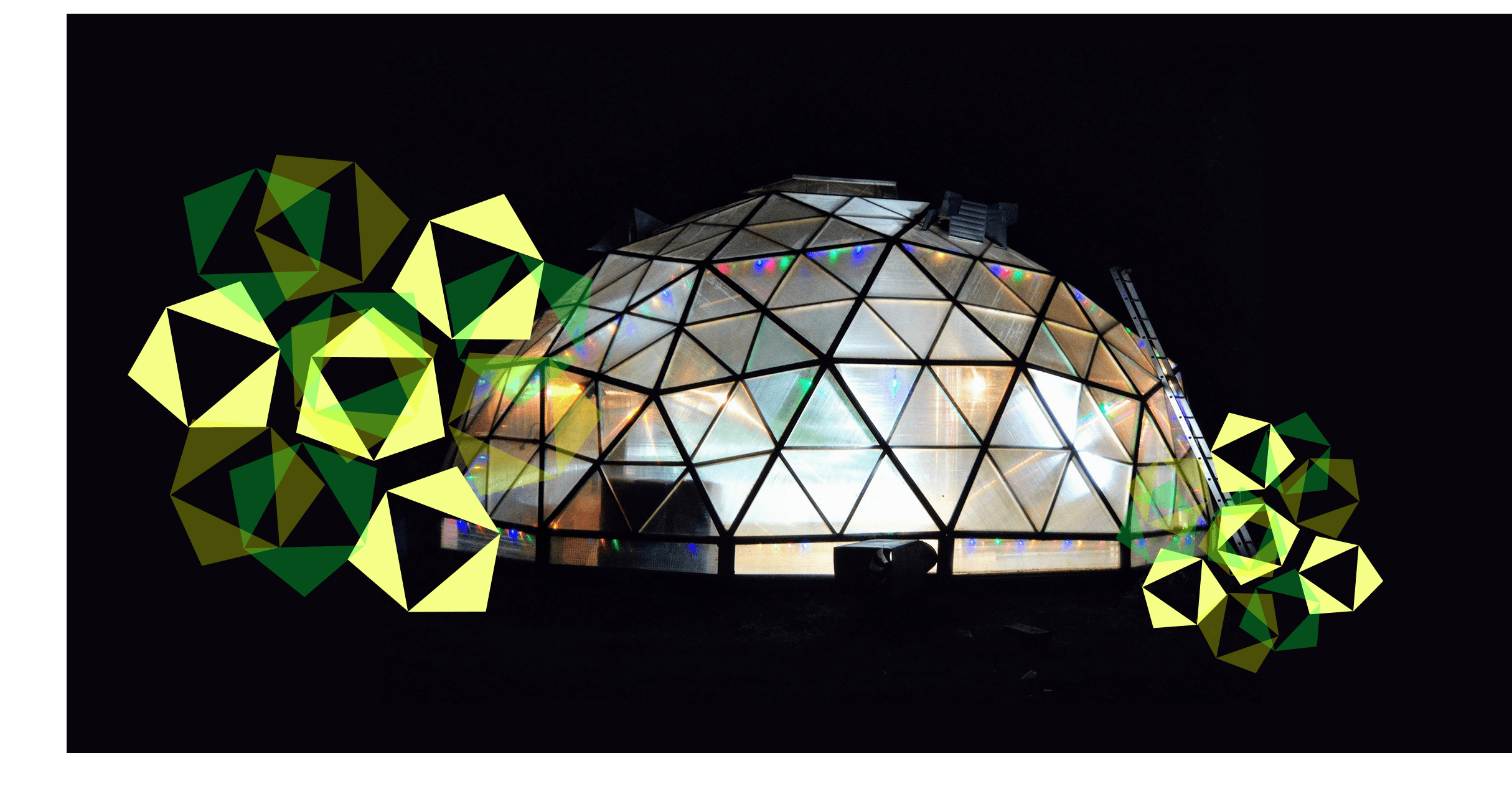

Born from the tensions between ecological sustainability and technology's growing presence in our everyday lives, this project aimed to create the supports for the operational needs of the GrowDome network; a series of geodesic domes dedicated to hydroponic crop production and hubs for community-weaving. In the face of increasing climate uncertainty and fragmented food systems, GrowDome represented a reimagining of agricultural and community infrastructure for the future, one that combines community care, technological development, and mutual growth.

📸 Project Snapshot

| Role | Research, Participatory Design, System Design, Process Design, UX Design, UI Design, Project Management |

| Context | Dublin City Council, D.S.A. Social Enterprise Industry Collab., 2015 |

| Year & Duration | 2015, 12 Weeks, 4 Sprints |

| Team | Multidisciplinary team with designers, engineers, community stakeholders |

| Tools / Stack | AngularJS, Node.js, MongoDB, OpenShift, Microcontrollers (sensors and actuators) |

This was infrastructure work. We were building for emergence and creating the minimum digital scaffolding for new kind of agri-social commons. The dome and it's surroundings was a place for collective imaginary [link to infrastructures] where community could gather, converse, imagine, explore and celebrate together.

The design of the GrowDome platform emerged not purely from best practices, but from what was needed to hold the pieces together: data, plants, roles, learning, coordination. It also had to make sense to people.

The Challenge / Opportunity

How can we develop a practical "alternative sustainable collaborative system" (ASCs) that tackles multiple interconnected challenges simultaneously? Such a system would need to play a part in helping to secure our food future while regenerating abandoned and underproductive lands. The approach should contribute to climate stability, drive economic growth, and alleviate poverty - all through collaborative, inclusive, and equitable methods.

The central challenge was not simply to "design a digital solution," but to uncover how a community-led, ecologically embedded space—the GrowDome—could become, not only a sustainable business (a social enterprise), but also a local resource - for food production, collective learning, and social connection. Part 'social farm', part 'social innovation', part 'social enterprise' - this meant supporting:

- the natural rhythms of plant cycles,

- the technical rhythms of crop production and scheduling, and

- the relational practices / 'social technologies' unfolding in each dome with dialogue, learning, participation, shared care, community weaving and futures visioning.

"The project was a question: How do we build something durable, digital, and useful at the confluence of a garden, a classroom, and a network? The GrowDome isn't just a structure - its a space for learning, conversations, growing food, relationships, and community initiatives. Our challenge is to find a minimal digital shape that could support this emerging pattern across multiple domes."

Digital technology was identified not as an overlay of control, but as a quiet infrastructure for growth of agency, autonomy and the network. What we were helping to build was a tool to support a community as they navigated the complex interplay between food, people, place, data and sustainable income.

The broader opportunity - in keeping with the prerogatives of institutional actors - was to uncover and prototype a scalable, values-aligned model that could replicate across Ireland, linking a constellation of local domes acting as nodes in a decentralised, living agri-social network.

Tensegrity as Design Principle

The GrowDome's geodesic structure became our design metaphor. Buckminster Fuller's concept of tensegrity—the balance between tension and compression that creates strength with minimal material—guided our approach to building both technical systems and community relationships. Just as Fuller's geodesic domes achieved structural integrity through distributed forces, we aimed to create a lightweight but resilient framework that could support robust technical infrastructure while nurturing collaborative learning between people, nature, and technology.

"This is about more than designing a system to grow crops. We are tending the soil of relationships, learning, and scaffolding spaces where community can root, speak, and thrive."

Research & Discovery: Understanding the Living System

Our starting point was ethnographic immersion. The team spent time in the initial GrowDome space—observing planting cycles, attending community events, and sitting in conversation with growers, volunteers, and community members. This wasn't user research in the traditional sense. We were learning to read a living system.

What emerged was a complex web of interdependencies. The domes weren't just production facilities—they were spaces where multiple rhythms overlapped:

- Ecological rhythms: Plant growth cycles, seasonal changes, environmental conditions requiring constant monitoring

- Operational rhythms: Harvest schedules, crop rotation, resource allocation, maintenance needs

- Community rhythms: Events, learning workshops, volunteer coordination, relationship-building

The challenge wasn't to optimize any single rhythm but to create infrastructure that could hold space for all three without flattening their complexity.

Participatory Design as Method

We approached this work through participatory design workshops with GrowDome staff, volunteers, and community stakeholders. These sessions weren't about gathering requirements—they were spaces for collective sense-making about what the network needed to become.

Key tensions surfaced early:

The efficiency vs. emergence tension: Institutional partners wanted scalable, replicable models. Community members valued adaptability and local autonomy. How could we build infrastructure that supported both?

The digital divide tension: Not all community members had equal access to technology or digital literacy. How could we build tools that enhanced rather than excluded?

The knowledge authority tension: Who decides what counts as legitimate knowledge in an agricultural system? Scientific data? Grower experience? Community wisdom?

These weren't tensions to be resolved but design constraints to be honored. The system would need to be flexible enough to hold multiple forms of knowing and organizing.

Design Principles & Approach

From our research, we developed core design principles that guided the technical work:

1. Minimal Viable Infrastructure

Rather than building comprehensive systems upfront, we focused on creating the minimum digital scaffolding necessary to support emergent practices. This meant building for adaptation rather than completion.

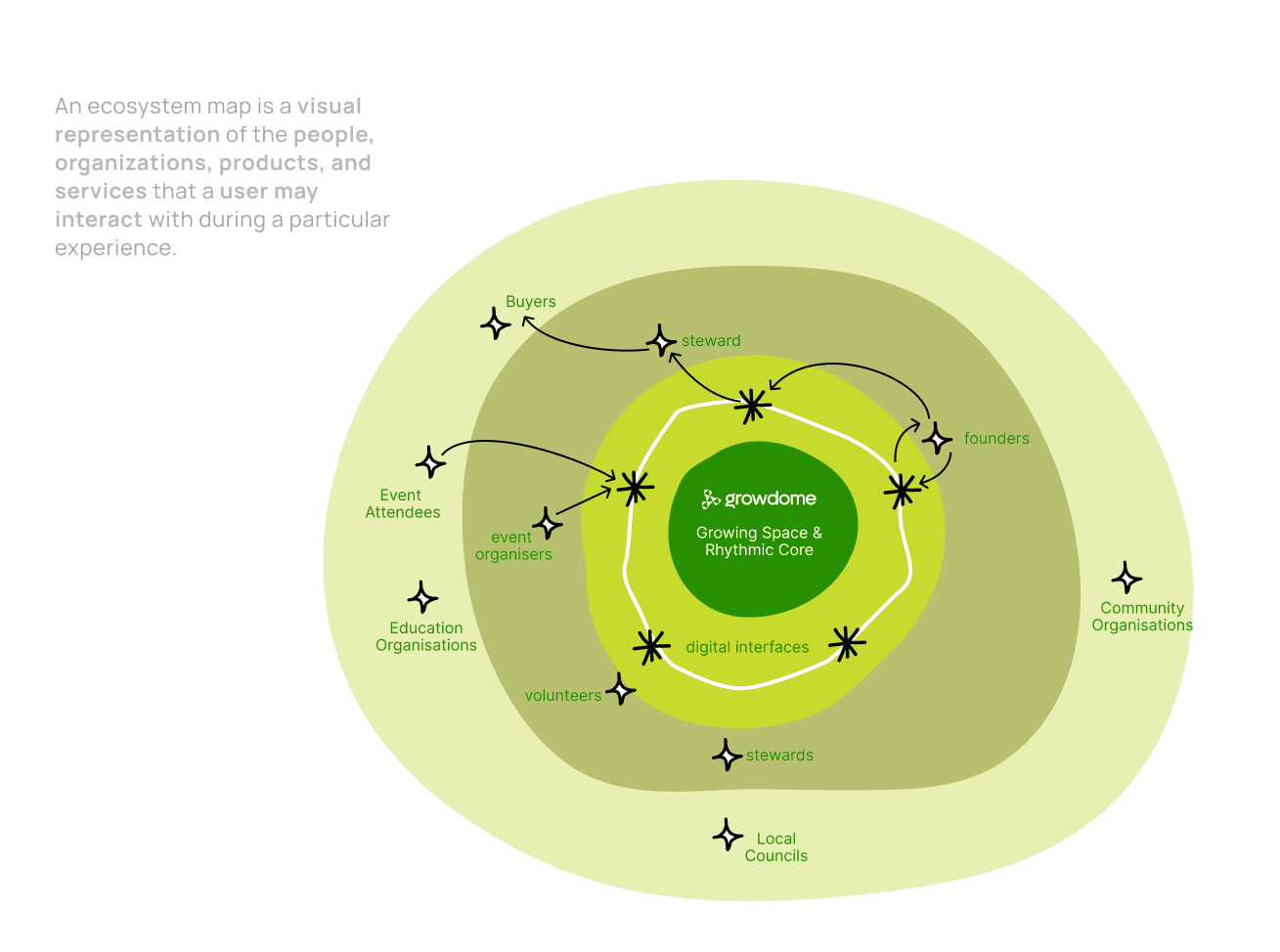

2. Distributed Agency

The platform needed to support autonomy at the node level while enabling network-level coordination. Each dome would maintain its own rhythms while contributing to collective learning.

3. Multiple Ways of Knowing

The system would hold space for quantitative sensor data, qualitative grower observations, and community knowledge—treating each as valid and valuable rather than privileging technical data.

4. Technology as Support, Not Control

Digital tools would augment human judgment rather than replace it. Automation would handle routine monitoring while preserving space for grower expertise and community decision-making.

These principles reflected our understanding that we were building infrastructure for a commons—a shared resource requiring careful stewardship rather than extractive optimization.

What We Built: A Socio-Technical System

The GrowDome platform combined several interconnected components:

Environmental Monitoring & Data Infrastructure

We designed and built a network of sensors and microcontrollers to track environmental conditions across the domes:

- Temperature, humidity, pH levels, light intensity

- Real-time data streaming to a central database

- Historical trend analysis and anomaly detection

- Mobile alerts for conditions requiring attention

This wasn't just about data collection. We were building a feedback system that could surface patterns invisible to individual growers—correlations between environmental conditions and crop outcomes, early warning signals for system stress, insights for improving yields.

Crop Management & Scheduling System

The platform supported the operational complexities of hydroponic production:

- Planting schedules aligned with harvest targets and community needs

- Crop rotation planning to maintain system health

- Resource allocation tracking nutrients, water, seeds, equipment

- Harvest forecasting to support community food distribution

These tools supported coordination without centralized control. Each dome could manage its own operations while sharing insights and resources across the network.

Community Engagement Platform

Beyond production, the domes were community spaces. The platform supported:

- Event calendar for workshops, gatherings, volunteer opportunities

- Learning resources capturing and sharing growing knowledge

- Volunteer coordination matching people to tasks and rhythms

- Story collection documenting the social life of the network

This component treated relationship-building as infrastructure work—recognizing that the network's resilience depended on social bonds as much as technical systems.

Knowledge Garden: Collective Learning Infrastructure

Perhaps the most experimental component was what we called the Knowledge Garden—a space for capturing, organizing, and sharing collective learning across the network.

This wasn't a traditional documentation system. It was designed to support multiple forms of knowledge:

- Sensor data patterns and technical observations

- Grower stories, intuitions, and experiential learning

- Community reflections on social dynamics and collaboration

- Links to external resources, research, and inspiration

The metaphor of a garden was intentional: knowledge would grow, cross-pollinate, and evolve rather than being filed away as static documentation.

Technical Implementation

Stack: AngularJS (frontend), Node.js (backend), MongoDB (database), OpenShift (hosting), custom microcontroller systems (sensors/actuators)

Architecture: Modular, API-first design enabling independent deployment and evolution of components

Data Philosophy: Federated approach where each dome maintained control of its own data while contributing to network-level learning

Accessibility: Responsive design supporting mobile access for growers working in the domes

Reflections: What This Work Surfaced

Looking back, this project raised questions that continue to shape my practice:

On Participatory Design in Practice

We aspired to design with the community, not for them. But participatory processes require time, trust-building, and sustained engagement—resources that weren't always available within project timelines and institutional constraints.

The tension: How do you honor participatory ideals while also delivering working systems within real-world constraints?

I learned that participatory design isn't an all-or-nothing proposition. It's about creating spaces for meaningful participation where possible while being honest about the constraints we're working within. Sometimes that means building something quickly and iterating based on feedback. Sometimes it means slowing down to involve more voices. The key is transparency about trade-offs.

On Technology and Power

Digital infrastructure isn't neutral. The choices we make—what to automate, what to measure, who has access—encode power dynamics and shape possibilities.

In the GrowDome context, we had to navigate:

- Data ownership: Who controls the environmental data? The sensor readings? The community knowledge?

- Decision authority: When should systems automate decisions vs. defer to human judgment?

- Access and inclusion: How do we ensure technology enhances rather than excludes?

The learning: Infrastructure design is always political. Being explicit about values and power dynamics doesn't make them go away, but it creates space for more intentional choices.

On Scaling and Replication

The institutional imperative was to build something "scalable"—a model that could replicate across Ireland. But community-rooted initiatives resist clean replication. What works in one context depends on local relationships, resources, and rhythms.

The question: How do we support network growth without flattening local particularity?

We tried to address this through modular architecture—building components that could be adapted and recombined rather than replicated wholesale. But there's deeper work here around what it means to scale community infrastructure. Sometimes the answer isn't replication but pattern sharing—helping other communities learn from our process rather than copy our solution.

On Urgency and Sustainability

There's a particular challenge in building community infrastructure within time-limited project cycles. The GrowDome network needed systems that could outlive the initial project funding and adapt as community needs evolved.

We built for longevity—choosing open-source technologies, documenting extensively, training community members in system maintenance. But the fundamental tension remains: how do we build enduring infrastructure within short-term project windows?

What I learned: Sustainability isn't just about technical choices. It's about embedding knowledge, building local capacity, and designing for eventual community ownership. The technology is secondary to the social relationships that sustain it.

On the Role of the Designer

This project challenged my understanding of what it means to be a designer in community-centered work. I wasn't just designing interfaces or systems—I was participating in infrastructure-building as a form of care.

The role shifted fluidly:

- Facilitator: Creating space for community voices in design processes

- Translator: Bridging between technical possibilities and community needs

- Builder: Writing code and configuring systems

- Gardener: Tending relationships and supporting emergent patterns

The insight: In socio-technical systems, design practice expands beyond artifacts to include the quality of relationships and the health of processes. Success isn't measured only by what we built but by how we built it and who it serves.

Design Tensions & Open Questions

Some tensions from this work remain unresolved for me:

Institutional Agendas vs. Community Autonomy

Social innovation projects often sit at the intersection of institutional interests (scalability, replicability, impact metrics) and community needs (autonomy, adaptation, dignity). How do we navigate this without compromising either?

Efficiency vs. Care

Optimization frameworks—even well-intentioned ones—can flatten the relational work that makes community systems resilient. How do we design systems that make space for care rather than just productive efficiency?

Expertise and Power

Who gets to decide what the community needs? This project brought me face-to-face with the limits of expert knowledge and the importance of lived experience. But it also revealed the complexity of truly participatory processes. I'm still learning how to hold this tension.

Building Infrastructure Under Crisis

There's a particular pressure in climate-related work—a sense that everything is urgent, that we're running out of time. But urgent timelines can reproduce extractive patterns. How do we move quickly while also moving carefully?

These aren't abstract philosophical questions. They shaped daily decisions about what to build, how to engage, and what to prioritize. They continue to shape how I approach community-centered technology work.

Outcomes & Impact

What We Delivered:

- Working environmental monitoring system deployed across GrowDome sites

- Integrated platform supporting crop management, community events, and knowledge sharing

- Training and documentation for community maintenance of the systems

- Framework and design patterns for expanding the network

What The Network Gained:

- Infrastructure supporting operational efficiency without sacrificing community values

- Data-driven insights improving crop yields and resource use

- Digital tools enhancing rather than replacing human connection

- Foundation for network growth while preserving local autonomy

What I Gained:

This was formative work for me. It was my introduction to:

- Participatory design in practice—both its power and its complexities

- Systems thinking applied to socio-technical design

- Community-centered technology as a design discipline

- The intersection of ecology, economy, and technology

More importantly, it instilled questions that continue to guide my practice: How do we build infrastructure that empowers rather than controls? How do we design for adaptation rather than completion? How do we honor complexity while still shipping working systems?

The GrowDome work taught me that technology practice can be a form of care when approached with attention to power, relationships, and long-term sustainability. That lesson shapes everything I've done since.

Contemporary Context: Why This Work Matters Now

A decade later, the themes we explored in GrowDome feel more urgent than ever:

Food Sovereignty & Climate Resilience

As climate impacts intensify, local food systems and community-led infrastructure become critical resilience strategies. The work of building decentralized, adaptive food networks is now mainstream conversation.

Platform Cooperativism & Data Solidarity

The questions we grappled with around data ownership and federated governance connect to contemporary movements around platform cooperatives, data commons, and algorithmic accountability.

Community Technology & Civic Infrastructure

There's growing recognition that technology infrastructure for communities requires different approaches than commercial product development—centering care, autonomy, and long-term sustainability over growth and extraction.

Post-Growth Economics

The GrowDome model—community ownership, regenerative production, mutual care—aligns with emerging post-growth and degrowth frameworks that center wellbeing and ecological health over endless expansion.

Looking back, we were exploring questions that the tech industry is only beginning to confront: What does it mean to build technology in service of communities rather than markets? How do we design infrastructure that supports thriving rather than just efficiency?

Key Learnings

On Technical Practice:

- Modular, API-first architectures support adaptation and distributed ownership

- Real-time data systems are only useful if humans can act on insights

- Open-source technologies and thorough documentation enable community sustainability

- Simplicity beats comprehensiveness when building community infrastructure

On Community-Centered Design:

- Participatory processes require time, trust, and sustained engagement—resource constraints are real

- Design decisions encode power dynamics—being explicit about values helps navigate them

- Community needs and institutional agendas often conflict—transparency about trade-offs is essential

- Infrastructure-building is care work—the quality of relationships matters as much as technical solutions

On Systems Thinking:

- Living systems resist optimization—design for emergence rather than control

- Multiple rhythms coexist in community spaces—infrastructure must hold space for all of them

- Scaling isn't about replication—it's about pattern-sharing and network learning

- Sustainability depends on social bonds as much as technical choices

On Design Ethics:

- Technology isn't neutral—all design choices have political implications

- Efficiency frameworks can flatten the relational work that makes systems resilient

- Expertise has limits—lived experience is valid knowledge

- Building under urgency can reproduce extractive patterns—speed requires care

Links & Resources

- GrowDome Initiative: Community-led network of geodesic domes for hydroponic food production and social connection

- Dublin City Council: Project partner providing site access and institutional support

- D.S.A. Social Enterprise Industry Collaboration: Cross-sector initiative supporting social innovation

- Related work: Co-Creating a Digital Ecology: Reflections on Community Infrastructure (coming soon)

Tags

Community Infrastructure | Participatory Design | Socio-Technical Systems | Food Sovereignty | Environmental Monitoring | IoT & Sensors | Knowledge Commons | Platform Cooperativism | Regenerative Design | Social Innovation | Systems Thinking | Care Ethics | Community Technology | Civic Tech | Urban Agriculture | Climate Resilience